On

Saturday, May 2, the Grateful Dead arrived at Harpur College in

station wagons after driving 130 miles from Alfred State College. The

night before at Alfred, one fan recalled "hanging out with Phil

and Mickey as they loaded the station wagons to split after the

show." Ned Lagin spotted them at MIT a couple days later: “Jerry

was driving a rented station wagon with the guitar amplifiers and

everything in the back.” There was sure to be an equipment truck

driven by the crew as well, but in 1970 a Dead tour was still a

largely DIY operation.

It was

Spring Weekend at Harpur (as it had been at Alfred), and many events

were afoot over the campus. (Note: back in 1965 the campus officially

became the State University of New York at Binghamton, but the

undergrad liberal arts college was still known as Harpur College,

which is the name I'll use here, deferring to tradition.) Students

could attend a raft race, a road rally, a buffet dinner, a Sunday

afternoon picnic, and more.

The

Dead had been booked to play the festivities along with Pentangle and

the Paul Butterfield Blues Band - and later in the week, the

Incredible String Band and James Taylor. The Dead were the most

expensive band: their fee was $4,000, but according to the student

paper, tickets would be $1.50.

One

student said, “Harpur's concert board did its best to bring in

groups that were on the cutting edge of what was happening.” The

concerts were sponsored by the Convocations Committee (the student

events group) and the Student Center Board. Convocations grandly

announced that they were able to offer such low ticket prices because

“the committee has met its budget requirements for the year. It is

able to forego profit necessities.”

On May

1, Pentangle played a two-set show in the men's gym at 8:00, with

reserved seats; Paul Butterfield then played a dance in the women's

gym at 10:30. (Those shows were $1.00 each.) On May 2 the Dead were

scheduled in the men’s gym at 8:30, with no seats. (The student

paper alerted ticket-buyers that "the length of the Dead's set

has not yet been determined." On the same night, the obscure Jam

Factory were playing a dance in the women’s gym, which only cost

fifty cents but was probably not well-attended.

Some

background on the week's lineup:

(This

ticket says $3.00. The newspaper didn’t announce any increase in

price for the concerts, so I’m not sure why the ticket price is

double.)

The

Dead were on a two-week tour, playing mostly colleges in the

Northeast. They'd started the day before, May 1, at Alfred State

College, which had not been very well-attended. One attendee says, "I

think there were maybe 50 people at the show." Another recalls

that Harpur was the “second

show in this format, the first at [Alfred] a flop. They did not have

the supplies or the "spirit" of the crowd on the Dead side

of Harpur.”

On

this tour, the Dead were expanding their usual format. Since February

they had been playing short acoustic portions, usually about six

songs, within their electric shows. But in April they decided to take

another step and open their shows with a whole separate acoustic set,

about an hour long. They practiced these in a few gigs at the Family

Dog:

Not

only that, but they decided to have the New Riders of the Purple Sage

open their shows on the tour, rather than other opening bands as

usual. Although Garcia and Hart had been playing in this group with

John Dawson and David Nelson for the past year, it was still

unrecorded on album and unknown to the public outside the Bay Area,

and the country-rock style with pedal steel was totally different

than what Dead fans might expect.

The

JGMF blog points out that on May 1, the New Riders opened the show,

followed by the acoustic Dead. This turned out to be unwise, as the

already-small audience left in droves.

Philip

Oby recounts how the Alfred audience diminished: "The show

started around 8 PM. Most of the people there at the beginning of the

show were unfamiliar with the Dead and had no idea what they were

getting into. The show opened with...the New Riders of the Purple

Sage...and during the break at the end of a very solid set, the

audience dropped from about 250 people to around 150 hearty souls. I

guess they thought it was country music. The next set was acoustic

Dead... [When it] ended, the band took a break and again the audience

was cut in half, so there were 50 - 75 knowledgeable souls left. By

now it was almost 11 PM... The Grateful Dead came onstage and Jerry

walked up to the mike and said: “I guess all we have left now are

the connoisseurs.”"

Seeing

the audience flee was not something the Dead were used to. So on May

2, they switched to the acoustic Dead – New Riders – electric

Dead set order they would stick to for the next few months. Partly

this may have been to greet the audience with something more

"Dead-like" at the start of the show; and partly it may

have made more sense equipment-wise to set up the louder electric

bands after the acoustic set. But Garcia seems to have seen the new

set order as an artistic concept, building the show from quiet to

heavy music: "We start off with acoustic music and then the New

Riders...and then we come on with the electric Dead...and it's six

hours of this whole development thing. By the end of the night it's

very high." (As reviewer Tom Zito would put it, "Concerts

started with acoustic instruments and gradually built into an

overwhelming electrical wave.")

Soundman

Bob Matthews recorded these shows. (Bear, who usually handled

recording, was legally stuck in California at this point after the

New Orleans bust, so Matthews went out on this tour with the Dead.)

Matthews had been producing the Dead's work in the studio over the

past year, so they trusted his engineering skills, but on the road he

seems to have been content to make a quick rough-and-ready tapemix of

their shows. Oddly, Matthews' tapes survive from the start of the May

tour (May 1-2) and the end (May 14-15), but not from any of the shows

in between, a sad loss.

There

was also a light show, a group called

"ICC Sound Union" from NYC. Not much is known about them

(I'm not sure if they regularly did light shows at Harpur, or just

came for the Dead concert). The newspaper review mentions images and

cartoons shown in the electric set. Steve Rosen, working in the light

show, recalled that “Mickey Hart left his drum set in the gym and

we returned it to him at their motel after the show!”

There

were plenty of Dead freaks around Binghamton. If people didn't hear

Dead albums from their friends or neighboring dorm rooms, they could

perhaps hear them broadcast on WHRW, the student radio station on

campus. Word of the Dead was also percolating around the area from

their NYC shows. One showgoer recalls: "My first Grateful Dead

show... A few months later, I entered Harpur College as an incoming

freshman... I heard about The Dead two years prior listening to

Allison Steel, ‘The Nightbird’ on WNEW radio NYC. Used to stay up

late simply to catch ‘The San Francisco Sound’, the bands she

played on her show. My favorite was The Dead!... The Harpur show was

everything to me."

The

men's gym at Harpur had just recently been built, opening in 1969.

The gym capacity was 3500, although there's no record of how many

people attended this show. (One attendee says there were "just a

few hundred," which seems unlikely; another says "maybe a

thousand," another says it was "packed.") Sal Caruana,

a concert staffer, recalls that due to the students' dislike of

campus security, "in their place groups of student volunteers

were often asked by event organizers to be ticket takers, ushers and

crowd-controllers if needed, and on the night of the Dead concert

many of the members of the TAU Alpha Upsilon fraternity were serving

in these functions." (At least a couple of the guys who served

as "security" for the show were also volunteers at the High

Hopes Drug Counseling Center at Harpur.)

One memory of working the show from Richard Block: "I was a student at Harpur College in Binghamton back then and had the best work-study job in the world -- I got to do the lighting for this show (and all the other concerts for three years.) They did this show differently; as always it was in our gymnasium, but instead of setting up the stage against the long wall and filling the gym floor with folding chairs, they set the stage up away from the wall to allow room for the Joshua Light Show equipment [sic] doing a rear projection light show behind the stage. Then they just left the gym floor empty for standing. Jerry Garcia asked me not to use our follow spots much on the band -- he said there was enough flood lighting on the stage and since he wanted to see the audience we should light them with the spots. The air was pretty thick up there on the spot light platforms and a number of police officers were roaming the audience, looking for smokers, so we would find one of the officers, zoom the spotlight in on him, the beam narrowed down to the size of his head, and follow him around the crowd until he got annoyed and headed for our scaffold, but somehow there was no one on the scaffold by the time he got there. Without a doubt the best concert we ever had there (and we had some amazing ones.)"

Richard

Wolinsky wrote a review for the school paper (the Colonial News)

describing the show. He set the scene: “Waiting

at the door. Tons of freaks waiting also. Painted. Tripping. Stoned.

The doors open. A mad rush for the floor. Balloons fly through the

air. "Clear for an aisle." "Anybody got any matches?"

"No Smoking." "Anybody want Electric Wine?" Whoo.

Whoo. Screams. A Bird Call.”

Other

memories from setlists.net: “A

cold wet Southern Tier night in a brand new gymnasium. Deadheads

converged from all corners, children played, hippies danced, frisbees

flew and the Hog Farm(?) came off the day-glo buses to do their light

shows (on overhead projectors with colored water).” “I

remember lots of people taking hits from what turned out to be spiked

jugs of wine as we entered.” “It was my first Dead show, but

there were many, many Deadhead veterans there.”

Another memory of the pre-show festivities: "The Hog Farm was DEFINITELY there as a prelude to the 5/2/70 DEAD show. I provided them with the location of where the science building was and shortly afterwards they showed up with a large tank of Helium which two guys hauled onto the student center stage where their light show was proceeding... Under the backdrop of what looked like white parachute material people could come up to a microphone, take a huge hit of Helium and give a short speech. This went on for quite some time until the tank was empty. Needless to say there were drugs involved and tremendous amounts of laughter."

ACOUSTIC

|

| Acoustic Dead 5/2/70 |

The

tape opens with tuning, chatter, and an excited crowd. Pigpen asks

the audience, “How come things are so strange around here?”

(According to

some listeners, in the background before this Lesh asks, "How

many drops did you put in my cup?" Someone replies, "I put

six." "I'm gonna be so far out!" Lesh says. However, I

can't make this out.)

Garcia

is more concerned with the sound levels: he asks the crowd, "You

people hear these guitars?" then asks Kreutzmann, "Hey

Bill, can you hear the guitars?" then tells Matthews, “Guitars

louder in the monitors please, Bob.” Lesh is on a turned-down bass,

and it’s Kreutzmann’s turn on drums. (He and Hart would alternate

as the sole drummer in the acoustic sets from show to show.)

After

more strumming, Garcia isn't quite satisfied: "We could still

have more guitars in the monitors, Bob." "Back monitors!"

Pigpen calls. (Some hear this as "Fat monitors!") Someone

in the crowd is trying to get Garcia's attention, with no luck: "You

want me? Sorry, man." But soon the band's ready: "Okay,

that's it," Garcia says. Pigpen tells them: "Have at it!"

They

start with an energetic ‘Don’t Ease Me In,’ Pigpen blowing on

harmonica. This had been their first single back in 1966, but they’d

only just started playing it again as an acoustic song in March.

Garcia encourages Pigpen before the harmonica solo: “Do it!” (You

can hear Weir scatting "da-da-da" quietly as the solo winds

up.) Pigpen hadn’t wanted to come out in the acoustic set the day

before, but he’s more active tonight. After the song ends Garcia

asks Pigpen, “Hey, you want to play a little bit of organ on ‘I

Know You Rider’? Nice and quiet, man!”

A slow

acoustic ‘I Know You Rider’ follows, with trio singing and very

quiet organ. In early 1970, the audience likely would not have known

this as an old Dead standard (unless they’d been to other shows in

New York lately), so this may have been the first time many of them

heard the Dead play it. (The same would be true of most of the songs

in this set.) In retrospect, it’s one of the first times Garcia

slowed down the original Dead arrangement of a song (something also

heard later in the show with 'Cold Rain'). He also adds the standard

folk verse, “I’d rather drink muddy water, sleep in a hollow log”

in these acoustic Riders. (Here he sings it with more emphasis than

the headlight verse, throwing off his timing coming back to the

chorus.)

After

Garcia tunes up, they continue with the brand-new ‘Friend of the

Devil,’ which had just debuted back in March. The bass & drums

are barely present in the background, making the guitar interplay

stand out.

Afterward

there's a bit of banter with the audience - "the demon rum,"

Pigpen comments. Garcia & Weir decide on the next song:

Garcia:

“Whatcha got on your mind?”

Weir:

“Uhhh…how ‘bout we do…”

Garcia:

“Dire Wolf?”

Weir:

“Dire Wolf? Sure.”

The

crowd is getting increasingly rowdy, and the band seems amused by all

the commotion. "Try playing your guitar," Lesh says. Garcia

tells the shouting audience, “Everybody just relax, man, we have

you all night long!” This only encourages everybody to holler more,

and Garcia calls, “All right, all right…” Lesh is more

impatient: “How do you expect us to play music when you’re

screaming?” Weir joins in: “Cool it, you guys, cool it. You gotta

start acting like a mature responsible audience.” Garcia finds this

funny: “Don’t listen to him!” Someone in the band starts

mocking the audience requests in a silly voice (“Jerry, play St.

Stephen!”) which makes Garcia crack up as one girl gets excited.

But

they launch into ‘Dire Wolf,’ one of several songs in the set

that would appear on Workingman’s Dead a month later. (Until then,

everyone who heard the song called it ‘Don’t Murder Me.’) It's

a strong performance - Weir remarks during Garcia’s solo, “I

smell gunpowder,” and scats along.

Afterward,

Garcia asks Weir, “You wanna do one, what do you wanna do?” Weir

suggests "How about 'Beat It On Down the Line’?" This

wasn’t the most obvious choice for an acoustic number – in fact I

think this was the only time the Dead played it acoustically. The

Dead check the monitor levels again (Phil: "I don't know, it

sounds a little better. The balance is a little better. Try and turn

'em up.") Weir asks the crowd, “Hey can you hear the guitars

out front?” Garcia grumbles, “We can’t. Turn the guitars up on

the stage again, and also the voices. All of a sudden this stuff is

all very quiet again – until now it was really good.” Weir

concurs: “It’s all disappearing before us.” Then it’s time to

pick the BIODTL beats: Weir asks, “Hey Bill, how many? Pick a

number! Eight?”

‘Beat

It On Down the Line’ was a song familiar to the audience from the

Dead’s first album, and they greet it with a cheer. It would also

be the only song in the acoustic set where Weir was the lead singer.

It works all right as an acoustic song, despite some vocal excess.

Pigpen plays some quiet organ, and Weir tells Garcia “Rock on out”

before the solo. (The newspaper review calls it “really

fantastic.”)

Garcia

cools the temperature down by going straight into ‘Black Peter,’

although it takes the band a minute to calm down, sync up, and settle

into it. Pigpen is a faint presence on organ.

Then

Garcia takes them into ‘Candyman’ without a pause. This was the

newest song in the set, which had debuted only a month earlier.

Unfortunately, the tape runs out after the first chorus, so most of

the song is cut. (On Dick’s Picks 8 this problem was solved by an

editing segue into ‘Cumberland Blues,’ which I think was also

done on old tape copies and perhaps on the FM broadcast.)

The

tape picks up again during a long pause, as Garcia puts down his

acoustic and picks up an electric (probably a Stratocaster). “Hey

Matthews!” he calls. “I need a microphone for the little

amplifier.” “Okay.” Lesh teases ‘Cumberland’ while this is

set up; David Nelson also comes out to tune his acoustic with Weir.

Garcia tells the crowd, “This is David Nelson who’s helping us

out with acoustic guitar.”

The

crowd claps along at the start of ‘Cumberland Blues.’ The Dead

had been playing this as a strictly electric number for months, but

they'd just started to try out the acoustic/electric blend onstage

and they liked the effect. The crowd likes it too, cheering after the

last break as Garcia generates some heat, and it gets big applause.

The

band ponders what to play next and settles on ‘Deep Elem Blues.’

This was another cover song briefly played in ‘66/67 that had

resurfaced in the acoustic sets in March ’70. I don’t think

Nelson had played the song with the Dead onstage before, but he was

familiar with it. It's the third prewar blues cover in the set; along

with the other blues-based songs, the Dead are showing their

influences.

After

some discussion and moving around, Garcia switches back to acoustic,

Nelson gets his mandolin, and John Dawson comes out. The end of the

set is near.

Garcia:

“Well it’s gospel time, everybody.”

Weir:

“Everybody take off your hats…or the men take off your hats,

ladies leave them on.”

Garcia:

“We’re gonna use a couple of New Riders for this here gospel

number. You got a microphone, Marmaduke?”

After

some tuning, “Here we go!” ‘Cold Jordan’ was then the only

gospel-quartet number in the set – ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’

wouldn’t be introduced for another month (and ‘A Voice From On

High’ was, for some reason, very rarely played). It’s

well-received by the crowd.

Garcia

says “Thank you boys,” and Nelson & Dawson split. He tells

the others, "Let's do 'Uncle John's Band' instead," and

they go right into an acoustic ‘Uncle John’s Band’ to close the

set. (Either Pigpen or Hart plays some extra percussion.) This song

had alternated comfortably between acoustic and electric renditions

in the past few months, and there's a sense of pride when they sing

it.

Garcia

says, “Thanks a lot. We’re gonna knock off for a little while and

bring the New Riders up here, and they’re gonna play for a while

and then the electric Grateful Dead’ll be back.”

Wolinsky

thought the acoustic set was “really fine” but the mood was

“Where’s

the electric?”

This isn't so evident on tape, where the crowd sounds quite excited,

punctuating the songs with screams. Compared to the Alfred show, the

Harpur audience is a lot rowdier, putting more energy into the set.

At times they're downright obstreperous. Part of the noise, as often

in those days, came from a battle going on in the audience between

the floor-sitters and the standers blocking their view. “Sit

down, people scream.”

But

one attendee captures the vibe: "I was a freshman at Harpur

College in the Spring of 1970, and I went to this show. It was my

first Dead concert. The first set was all acoustic, and...many in the

crowd seemed unprepared for the acoustic set. They kept yelling

things like "Get it on, man!" and Jerry and the boys had to

ask them to calm down and be patient---the electric stuff would come

later."

The

acoustic repertoire is still limited at this point, dominated by

Garcia's songs, with most songs repeated from one show to the next.

There's a rustic front-porch feel, heavy on folkie harmonies and

blues covers; this is the Dead in their simplest country guise. But

Nelson's involvement adds a new element: the Dead's acoustic set

becomes a more communal affair, with new guests showing up, Garcia

switching guitars, extra textures with Strat or mandolin, and nods to

Bakersfield, bluegrass, and gospel styles that would be expanded in

later months. (And musically, it also helps that Kreutzmann is

drumming tonight. Hart's clomping percussion had been distracting in

the acoustic songs at Alfred, but the drumwork in this set is always

fitting.) But one reason this acoustic set is so beloved is not just

the crowd energy, but all the intimate chatter with the audience –

once the electric set comes, there's noticeably a lot less

back-and-forth banter.

NRPS

|

NRPS photo from 5/7/70 - not from Harpur

|

|

| NRPS photo from 5/7/70 - not from Harpur |

The

New Riders of the Purple Sage were returning to the road after

apparently taking a few months off. (There are only a scattering of

shows in the winter, and this tour has the first circulating NRPS

tapes since October '69.) Dave Torbert had joined them on bass and

they'd worked up a regular repertoire of John Dawson's songs and some

well-known covers. But at this point they're still a "new"

band without that many gigs under their belt, and it shows.

The

crowd is very enthusiastic for the New Riders, and the set goes down

well. By Henry and Lodi, the audience is going nuts. (The combination

of a popular Creedence tune and Dawson dedicating a song to "anybody

in the audience that happens to smuggle dope for a living"

probably helps.) Then Dawson announces, “I tell you, we’re gonna

get Bobby Ace, formerly of Bobby Ace and the Cards off the Bottom,

heh, and he’s coming up here right now – he’s got his

guitar...”

Weir

comes out to sing on Sawmill, The Race Is On, Me & My Uncle, and

Mama Tried. He'd been an occasional guest in New Riders sets since

summer '69, and a few of his country covers were shared between the

New Riders and the Dead. (Three of these songs had been done in the

Dead's acoustic set the day before.) Weir gets the chance to indulge

his "Bobby Ace" country-singer persona, Dawson harmonizing

on all the songs, and the audience digs it.

The

set ends with The Weight (without Weir, although Garcia sings some

backing vocals). Dawson tells the crowd, “Grateful Dead coming on

in about 10-15 minutes.”

The

New Riders were well-received, their country style accepted by an

audience that had come to the show expecting the likes of Anthem of

the Sun or Live/Dead. There aren't many shouts for the Dead, anyway

(although there may be someone yelling, "Get to the electric

stuff!"). Even Wolinsky, impatient for the Dead, called the New

Riders "fine country music" and singled out some

"fantastic" highlights (Lodi, The Race Is On, The Weight).

Concertgoers remember their set fondly: "The New Riders were

terrific." "They were spectacular." "The Riders

at their peak."

I

don't think the set holds up so well on tape. It's rickety,

untogether country-rock with a lead singer prone to yelping. (Dawson

seems, well, pretty high.) The drumming's uneven, as Hart's not very

steady. Torbert is a solid base, but Nelson is understated to the

point of invisibility. It's all held together by Garcia's pedal

steel, taking most of the solos and adding a sweet frosting to the

music. But this is not the New Riders' finest hour.

Some

listening comments from the JGMF blog:

ELECTRIC

|

| 4/24/70 Denver - not from Harpur |

Unlike

the acoustic set and NRPS, the tape of the electric set is basically

in mono - much like the recordings on May 1 and May 14. In fact,

almost all of Bob Matthews' recordings on the road in early 1970 are

in mono, so it seems to have been his preference. This makes me think

the switch to mono at Harpur was Matthews' choice, not an accident as

people usually suspect. The mix is okay, although Weir’s guitar is

low, bringing Garcia to the fore. Pigpen plays organ through much of

the set, but it's very quiet, more felt than heard.

The

newspaper review: “Garcia

plays the first two notes of St. Stephen and the crowd goes berserk.

The light show flashed St. Stephen with horns and snake hair.”

The

tape comes in during the middle of ‘St. Stephen.’ (Apparently the

first two minutes of 'Stephen' on the Vault tape are just white

noise.) ‘St. Stephen’ almost never opened a set – in fact, the

last time had been at Woodstock in August ’69 (which had fallen

apart). The crowd hollers after the “another man spills”

cannon-blast. (“The

crowd fills in the album screams.”)

The jam is short and ramshackle, and after the last verse Garcia

segues right to the ‘Cryptical Envelopment’ intro, to the crowd’s

joy. (This was also rare: the last time they were paired had been

back on 4/23/69, and it would only happen once more on 5/15/70.)

After

a rather low-key 3-1/2-minute drum break (the crowd shouting them

on), the band storms back in with 'The Other One.' The rhythm's

strong, the band aggressive, Garcia flying on his Gibson SG, the

effect fierce and hypnotic. Weir churns out fuzzy chords while Lesh

prods everyone forward. There's a big crowd cheer when they quiet

down for the verse. The jam after the verse becomes more subdued and

delicate but gradually ramps back up to heaviness. Things get wilder

when Garcia sustains a long feedback note, drills into a droning

fuzz-concerto, and bursts back into the crazed theme lick. After the

second verse, more cheers when the band smoothly returns to

'Cryptical.' They stay quiet & slinky for a long time, ambling

along for a few minutes until Garcia plays a tense harmonics

transition back to “you know he had to die.” Good vocals and

feedback lead to a sudden explosion – the jamming turns intense,

Garcia's playing twisted and fractal as it turns in repeating circles

– “endless

and phenomenal. Garcia’s guitar is cosmic.”

Finally the jam winds down in quiet harmonics.

This

Other One suite is a close companion to the version at Alfred the day

before (the only piece the electric sets have in common). The May 1

Other One is also a great angry version, very similar to Harpur but

just a hair below in charged intensity. Tonight the band slides into

‘Cosmic Charlie,’ the usual destination out of 'Cryptical.' After

an amped-up start it's a standard version for the year with the added

twin-guitar riffs, played very carefully. “People

jumping up and down.”

Garcia

has to tune, so Weir says, “Hey, we’re gonna take a couple

minutes and tune up here.” I think the tape is stopped, so it’s

not that long before they start ‘Casey Jones.’ The audience is

silent when it starts, this being a new song to most of them.

Wolinsky calls it “a

song I don’t know. Someone told me it was the Train song.”

It’s a short and average version, but the crowd’s enthusiastic

when it ends. (For one witness, "my

most vivid memory was the crowd going absolutely bonkers when they

played Casey Jones.")

“People

flopping on top of themselves.”

Then

‘Good Lovin’’ opens with a short drum intro and some

bludgeoning guitars, Pigpen entering in a howl of feedback and the

others shouting their vocals. Pigpen calls “Groove a while!”

after the verses, and the drummers go into another drum duet (this

one more energetic than in the Other One). After 3 minutes the

guitarists come back over a frantic Latin-style two-chord rhythm.

(They were getting into this kind of thing heavily at the time –

compare the jam before the Other One on 4/15/70, or the jam after the

Eleven on 4/25/70.) Garcia blazes over a high-speed frenetic jam;

after a couple minutes Weir & Lesh drop easily back into the Good

Lovin’ chords behind him. [In the Miller copy there's a dropout at

9:34, covering a reel flip - it was quick, sounds like nothing's

missing, but Dick's Picks 8 edits out a small portion here.] Garcia’s

in the mood for a ‘Soulful Strut’ jam (you can hear him start to

tease it around 9:20) and pushes for it with some strident chords

around 10:20, blended with Good Lovin’, but doesn't quite get

there. (“Garcia

gives a break which almost goes into Lovelight but never quite makes

it.”)

After 11:20 Lesh tries to switch gears to ‘Feelin’ Groovy’ but

it doesn’t take. Instead the jam breaks down to a Garcia/drum duet,

then Garcia & Weir repeat the Good Lovin’ riff over & over

without Lesh until finally Garcia slows it down and they plow back

into the verse, to crowd cheers. “Pipes

and joints flow to the music.”

There's

long applause after the song – Lesh teases ‘High Time’ but that

song won’t appear. Instead, after some tuning they start ‘Cold

Rain and Snow’ (of course, it was raining outside during the show).

It’s immediately apparent that Garcia is out of tune. The others

hesitate, but he decides to tune on the fly while playing the song.

He can’t get in tune for the first 3 minutes, which certainly adds

a weird effect, but then he treats the audience to a very loopy solo

and some emphatic singing. Despite its problems, it's quite the

surreal version of this tune with a slam-bang finish. (Wolinsky, a

fan of the first album, called ‘Cold Rain’ “one of the best

things in the set.”) Wisely, more tuning follows the song. (It was

left off Dick’s Picks 8, but restored on the vinyl reissue.)

After

some chatter, they remind themselves of how ‘It’s A Man’s

World’ goes. “Have at it!” Pigpen commands, and they start the

song on the count of 6. This James Brown cover was the newest

addition to their electric set (they’d been playing it for less

than a month, and the song would stay in the repertoire only through

1970, so it's a rare piece). I think this is the first version where

they sing the "da-da-da" backing right at the start. Pigpen

sometimes loses his place in the verses, but makes it work. There's a

nice transition in the middle from Pigpen's groaning chant to a

Sputnik-like Garcia passage, which lights up this performance.

Previous versions (like 4/25) had a big Garcia solo, but here he only

gets a brief understated break. Pigpen dominates without leaving much

space for a jam, but Garcia still has some good bluesy playing under

the vocal, conjuring up a dark smoke-filled atmosphere, and the new

minor-key ending is great. The whole band shines in this one. "The

music comes on and keeps coming."

The

Dead are in a Motown mood, and they cheerfully carry on with ‘Dancing

in the Street.’ "Come on and dance around now!" After

some sloppy backing vocals, Garcia takes a slow-burn approach to the

jam. The intensity rises 4 minutes in, and Hart starts wildly banging

the cowbell. After 4:30 a Latin feel starts to creep in, which Weir

turns into a full-blown ‘Soulful Strut’ by 5:00 (formerly known

as the 'Tighten Up' jam). This one’s longer and more developed than

in Good Lovin’, stretching over 5 minutes, with Garcia taking the

theme through several phases, from speedy notes to choppy chords to a

fuzzy reprise of the melody. [There's a tape warble going 'zip' like

a stopped reel, at 8:40 on DP8 or 8:50 in the Miller copy, but it

doesn't sound like anything's cut.] The drums tumble, Garcia switches

his tone, and Weir & Lesh keep pushing the jam forward, not

wanting to let go. Around 10:30 Garcia swerves back to Dancing territory with some Cosmic Charlie-type chords that leap dramatically

to a Sputnik at 11:30 (sounding as much at home here as in a Dark

Star). (“Garcia

throws in a Dark Star riff I think.”)

This lasts a minute then blasts into ferocious Dancing chords, a

final stirring crescendo...and the jam almost fades out in a feedback

haze before Weir brings back the verses just in time. After his final

yell, the song finally ends with a triumphant burst of feedback,

which cuts at the end as the reel runs out. (Dick's Picks 8 patches

on the last few seconds from the 4/12/70 version here.)

This

amazing version of 'Dancing in the Street' follows two other

incredible performances in April. 4/12 (best-known from Fallout from

the Phil Zone) is more light-footed, fast & torrential, bursting

with ideas and quickly shifting from one phase to the next so it

doesn't hang onto one theme for long. 4/15 is very similar to Harpur,

with most of the central jam a lengthy Soulful Strut theme followed

by a Cosmic Charlie-type finale. It's telling how much of the Harpur

jam could come straight out of a Dark Star – the Soulful Strut

theme was shared between Dancing and Dark Star this year, as if the

two songs were interchangeable at the core. (Looking ahead a bit,

they'd be paired at the Delhi show on May 8, another night of magic,

as a single continuous suite.)

The

band decides it’s time for a break. Lesh announces: “Okay now,

you folks should all follow the fine example of the fellow over here

who got it on over here with his girlfriend, and we’re gonna take a

short break, and I want you to all feel each other for about ten

minutes while we… But we’ll come back and play some more, honest

we will.”

The

crowd collects themselves for more. “Everybody

gets water and runs through the rain; people look dazed. Some sitting

giving tripraps...”

It was in the 40s outside, so a little break from the heat and smoke

of the gym must have been refreshing. Student concert staffer Sal

Caruana recalled, “Between

the two sets there was an intermission, and in the intermission, a

lot of people went outside, and it was pouring and these people were

impervious to the rain, and that told you that they were really into

the music or really out of their skulls.”

When

the Dead come back to the wet audience, they waste no time heading to

the dark side. Hart’s gong ushers in the doomy intro of ‘Morning

Dew.’ It’s an excellent, heavy version – as Wolinsky says,

“totally controlled and superb.”

After

a little chatter, the Dead continue with another old tune off the

first album, ‘Viola Lee Blues.’ Although they’d played it a few

times since March, it was infrequent in their sets and starts

lumberingly. (The last version on 4/12 is like a lighter, more agile

twin to this one.) A lyrical stumble in one verse hardly matters; the

crowd cheers after Garcia's climbing spirals between verses. The main

jam starts very slowly and gradually picks up speed, very controlled

– as the pace picks up like a speeding train, by 10:00 the tempo is

racing, the band becoming liquid. By 12:25 chaos has descended and

they fall into the climactic meltdown, then snap neatly back to the

loping song riff at 13:15 to astonished cheers. (“Viola

Lee Blues with three buildups, the last ending with people screaming

and shouting and Garcia pulling the most phenomenal notes out of one

guitar.”)

Garcia delivers some final stinging licks before the last verse, and

the song closes with 90 seconds of howling feedback – the Dead in

fierce primal mode, harking back to the old days.

The

crowd starts a slow clap, and the band sings a soothing ‘And We Bid You

Goodnight’ with some quiet guitar notes and the audience clapping

along. The old funeral hymn offering comfort and salvation to the

dead is well-placed here, and it's easily the best version of the

year. It ends after 3 minutes, the crowd roaring. Garcia bids

farewell: “Thanks a lot, you people are too much.”

The

crowd stomps to bring them back (“no

one will let them go”)

but Sam Cutler comes out to tell them: “The Grateful Dead are very

tired. We have to go to Connecticut tomorrow and we’d like to

sleep, but we’ll be playing at the Fillmore East on the 15th of May and I think there are tickets still there, so come and see us

at the Fillmore East – we’re worn out, thanks anyway”

This

could be considered a short third set or a half-hour encore, the

weary band's last gasp. Either way, it heightens the intensity of an

already fired-up concert, and the apocalyptic feel of this closing

stretch has few rivals among Dead shows. Most of their shows at the

time ended with a rousing long Lovelight, always guaranteed to leave

an audience happy. The dark Feedback closers of yore were being

phased out, with just a few exceptions – the Caution>Feedback on

2/14, the Viola Lee>Feedback on 4/12, and likely some lost shows

such as 4/10 and 5/9.

But

now it's time for the band to depart, and the audience to return to

the everyday world. The last voice on the tape is someone on a

microphone saying, “What a pretty girl you are.” According to one

attendee, this was Phil: "He

was trying to pick up one of our friends there with us. She was

having none of it!"

AFTER

One

dead.net commenter recalls We Bid You Goodnight ending the show at

3am, and another witness recalls "the Dead went way past 2am. We

all did." The show had been scheduled for 8:30, and Wolinsky

reports that it was 5-1/2 hours long. If the show had started by 9pm,

it would have ended between 2 and 3. (The sets on tape add up to

about 260 minutes, so the setbreaks were likely considerably longer

than "10-15 minutes" each.)

Wolinsky

noticed some people sleeping, but this may not have been due to them

being worn out by the Dead. According to Sal Caruana,“The concert

staffers were all asked to remain until everyone had left the

building. When

the West Gym finally emptied around 1:30 a.m., there were eight

bodies left lying on the floor in various drug-induced states, and no

one on the scene qualified to assess or treat these individuals.

Students rushed to make frantic calls from the gym office to campus

security for help...and to local hospitals for ambulances.”

The

calls were met with indifference (which he ascribed to "hippie

payback"), so "we made a quick and frenzied decision to

load the students into our cars and race to the three area

hospitals... Once at the hospitals our victims were promptly accepted

and treated, and we were advised to go home. As we left, we realized

we did not know any of their names, and none had been recognized by

us as Binghamton students. News of the eight overdosers or their

outcomes never appeared in the campus paper or Sun-Bulletin... Though

fatalities were never confirmed, those of us who kept asking

questions heard one story or rumor repeatedly: three of the victims

had died and none of them had any Binghamton connections (they were

either Deadheads and/or students from other upstate colleges)."

(Personally

I think if there had been any fatalities from overdoses at a Dead

concert on campus, this would have been certain to make the news.)

Wolinsky's

review of the show was printed in the May 5 edition of the Colonial

News (along with a worshipful review of the Pentangle show, to which

he replied, "they didn't approach the Dead").

Some

more recent comments from Wolinsky were used in a 2020 Pipe Dream

article by Gabriela Iacovano on the show:

Wolinsky

raved about the show, “the finest concert I’ve ever seen.” Many

others there felt the same: “I've been to many shows; this was the

best.” “Best ever, of all of them I've been to.” “I can

testify that this was the best concert I have experienced in my 60

years.” “It

was certainly a life changing experience.”

Some

comments on the show from attendees in an NYT poll:

“As

I recall, the show started in the Harpur gym at about 9 pm with Jerry

playing with the New Riders for a set or two...they were spectacular!

The Dead then came out and played until 4 am or so. I especially

remember an amazing version of Saint Stephen. The Hog Farm denizens

including Ken Kesey were in attendance. I recall standing near the

stage in front of a huge tower of speakers with Jerry's solos

piercing my skull (I don't think that my hearing has been the same

since that night). It was a wonderful and surreal night on so many

levels.”

“What

a concert and experience that night at Harpur. The place was buzzing

and partying for hours before...a jug of wine with something (!) in

it was circulated...electricity in the air...I stood impaled by the

sound of Phil's bass in front of the tower of speakers at stage

right...the music just kept getting higher and higher....people in

front of the stage doing interesting things on top of a

parachute...what a night!!”

“If

you followed the Dead in those early years, you know how it was. The

Dead were just rocking like mad that night in the intimacy of the

gym. The music coming out at us like living waves of big time energy

seemed to last forever, loud as it was and near as the band was –

and the many-footed fans, wild and nonplussed, stoned and tripping

and seduced by it all, swaying and jumping and dancing to the push

and tug of the music like the band was the moon and we were a willing

body of water.”

“I

was a freshman at Cornell. Had tix for Pentangle but my friends

talked me into giving them away so I could experience the Dead. So

when the bus went by, I got on & then it all began. This was a

concert that changed my life. The music, the vibes, the politics, the

people were all new to me. They all validated for me how there are

alternate ways to see & live life - a value I still cherish.”

“I

was 16. I didn't partake of any of the festivities going on round me

cuz i didn't want to do something stupid... Pretty much wandered

about in open jawed amazement the whole time knocked out by it all.

We walked in on the Riders and at first I was 'what the hell is this'

but soon got it… After the acoustic sets I was beaming...they still

were as trippy as Anthem too. Been to a few concerts already

including Janis and Jimi but not like this. Remember really digging

Pigpen, and the most beautiful women I'd ever seen in my life. After,

we went back [to the dorm]...I know I didn’t sleep.”

(From

Reddit:) “After an amazing show the night before at Alfred, we

loaded into Wally’s bug and drove down to Harpur College, on Phil’s

insistence we come to this show. My memory is really fuzzy here, as

this was the first time I had tripped 2 nites in a row. I was really

overwhelmed by last nite's electric set, so during the acoustic and

NRPS sets, I just kinda wandered around meeting new people and

talking to myself - haha! You don’t really realize at the time you

are viewing history happening, as the band began their set. They

played dragon music that nite. It spiraled around and around and

trembled and exploded (!). We danced and jumped and screamed! We

laughed and cried. It

was amazing. But not...until a few years later when I heard my first

bootleg of the electric show that I realized just how good it was.”

A

longer testimony from Hank Keiser on dead.net:

"Winter

was slowly exiting the Southern Tier; snow had turned to ice had

turned to mud. Binghamton was a dreary area; clouds came down the

Susquehanna Valley from the Great Lakes just about every day... But

we welcomed every Spring with a weekend of concerts. This spring

brought The Butterfield Blues Band, Pentangle, and The Grateful Dead.

"The

Dead show was going to be held in the new gym; I watched the sound

check that afternoon, they were having trouble with the power supply,

which was playing havoc with the monitors... [But] the New Riders

seemed to keep everything mellow. Monitors were fucking up, they

didn't care, unplug the whole thing and just play. No master

electrician in sight, no power schematics to be found. Patch and

pray. The recording engineer was more bugged than the band.

"8

p.m. rolled around, a high level of energy, frantic energy engulfed

the gym. Pigpen took the microphone and asked "How come

everyone's so weird around here." He'd never experienced a Binghamton winter - snow, ice, wind and acid, tons of acid. The crowd

remained on edge, Jerry sensed it, leaned into the mic and said

"Relax, we've got you all night long." And the gym erupted

in cheers as though a karmic dam had burst. The monitors were still

not right, and now the mics were shorting too. "More monitors,

Bob" Garcia asked. "Fat monitors" Pigpen chimed in.

"The

acoustic set lasted about 75 minutes, then NRPS came out with Weir

and Garcia...about that time the screen behind the band began to

flash "It's in the water" every 60 seconds or so. I looked

around and found someone with a goat skin. It was in the water. NRPS

was at their best, loose, easy, full of life. It was a mix of stuff,

including a few things that made their way on to Workingman's Dead in

a more polished style.

"There

was about a 15 minute break before the electric set began, long

enough for the edge to return to the crowd. I remember thinking

"When's it gonna happen?" It was stage, open floor, and

bleachers pulled out on the side. Really primitive lighting, maybe 20

lights in all. I could see the engineers, they weren't happy, they

had just lost a power supply... But they had the speakers right, and

the gym was filled note after perfect note.

"By

now the band was into The Other One, the edge was building, and then

it happened - Lesh hit the bass notes I'll never forget. And the

music exploded... I had my Dead Moment at Harpur. There were maybe a

thousand of us, open floor, no security, 4 foot high stage. And goat

skins."

Rumors

about the Dead's visit floated around the campus for years

afterwards. Deadbase reviewer Gregg Bucci, who went to school there

later on, wrote, "One of the stories I've heard is that the Dead

hung out in the new dorm room complex on campus during the afternoon

of the show and that people were dispensing liquid sunshine from

water pistols... It has also been said that following the show, which

was held in the gym, someone set up a volleyball net and the Dead

clowned around with the concertgoers." (This last story seems

unlikely. However, one showgoer says, "I

talked to Jerry that night and played soccer with Bob and Sam Cutler

and some roadies.")

The

Dead traveled on to Connecticut to play a free show at Wesleyan

University, then onwards to MIT, only to find that their spring tour

of Northeast campuses was coinciding with a nationwide wave of

college strikes over the invasion of Cambodia on April 30:

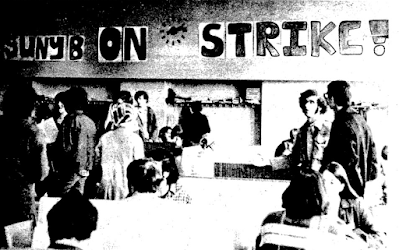

Harpur

was going through its own turbulence. Students remember the political

heaviness of the time: “This show at Harpur took place 2 days after

Nixon came on TV to announce that we had troops in Cambodia. Campuses

everywhere erupted…” “On campus we were either on "strike"

or soon to be due to the Cambodia incursion.”

The

university voted to go on strike on May 5 and classes were canceled

for the rest of the semester. (See this editorial.) But after a

couple of weeks, protests dwindled and many students simply went home

early.

(The

Colonial News was disappointed by the small turnout for a march in

Albany. "An Alfred University student standing on line at a

water fountain summed up his dismay at the demonstration. 'Harpur.

Everybody's from fuckin' Harpur,' he said.")

The

student paper went through changes as well: "Colonial" was

struck from the name Colonial News, and the next year the paper was

renamed Pipe Dream.

After

the Dead returned home, they made the unusual decision to share their

tape of the show. They had done a couple of live radio broadcasts

before (most notably 2/14/68 and 4/6/69), but in general they seem to

have kept their growing stash of live tapes to themselves. One

wonders: when they listened back to the Harpur show, what did they

hear? Perhaps, to them, it was a particularly high night, or the

first show where the new "evening with the Grateful Dead"

show format proved itself.

At any

rate, someone passed along the whole tape (acoustic, NRPS and all) to

KPFA in Berkeley, who broadcast it as part of their weekly series of

live shows. Radio taper Cryptdev recalls: “The KPFA broadcast

series was called "Stays Fresh Longer" and consisted of one

live broadcast every Sunday night… I remember the regular emcee of

the show saying that the Dead had provided the tape of the Harpur

show for broadcast.”

The

show was apparently also broadcast by WBAI in New York. One radio

listener has a different memory of the announcement: “Warren

Van Orden, the radio host for "Stays Fresh Longer," before

broadcasting the Harpur college concert...said up front that the

concert was recorded by KPFA'S sister station WBAI. So KPFA really

had no involvement with the initial recording.”

It may

have been first broadcast in June '70, although one person remembers

the show being broadcast later that September, so it could have been

repeated. It seems the whole show was broadcast in one night, despite

its length; Cryptdev says, “I

don't believe the DJ even broke in between sets - just let the whole

show play through.”

Another

listener recalls: “First heard the whole show on KPFA in

1970 and taped it off the air on a Sony open reel, copied it to

cassette.. After the show played at KPFA there were voices in the

studio yelling "play it again, play it again."”

Tapes

of the show made their way to many listeners. One, for instance: "I

played this reel recording of a '71 broadcast over and over in the

summer of '72, I realized this was a very exciting band that I wanted

to see... That tape did it, this was a really wild band, and it

really made me think about rock music differently..."

Back

at Harpur, the buzz around the show also remained strong through

word-of-mouth as showgoers passed its reputation down to newer Dead

fans:

“For

years we who had been there claimed it had been the best of the best

Dead concerts, and when one bootleg surfaced...even people who were

only able to hear what it had been became believers.”

"A

friend of mine, who had seen the Dead a bunch of times by then and

had tried to get me into them, was at the show. He told me it was his

favorite."

"I

remember people who were much more into the Dead than I was in 1971

talking of this show as monumental."

"This

was the concert that those of us who arrived in Binghamton the

following September were still hearing about in the fall."

“I

arrived as a freshman at Harpur a few months after this show, in

September 1970 and…everyone was talking about the Dead show. I got

a bootleg record of the concert, that has the title "Cowboy's

Dead" on the homemade album cover...”

Overall,

the 1970 Harpur concert schedule was considered a great success, with

numerous popular acts playing on campus. A Pipe Dream article on the

Convocations Committee from 9/15/70 summed it up: “Last year the

Grateful Dead, backed by C.C., played five straight hours through

smoke and din. Mountain, Arlo, and Phil Ochs loved the packed house.

The wild crowd paid no more than $2.00 a head for The Band and Tim

Buckley; and the Convocations Committee made profit on all of them.”

Naturally,

many people hoped the Dead would return and play at Harpur again - a

1971 article in Pipe Dream noted that "many people were

enthusiastic over inviting the Grateful Dead back this year."

The Student Center Board did their best to book the Dead again in

fall 1970; but the Dead would not return.

Pipe

Dream reported on 11/3/70, “No Grateful Dead”:

“The

Student Center Board regrets to announce that the Grateful Dead

concert, which was tentatively scheduled for November 19, will not

take place due to the fact that one member of the Dead group was

recently busted and will spend the month of November in jail. SCB

will attempt to book the Dead for a date sometime in December or

shortly thereafter.”

It

seems someone was telling a fib! (The Dead spent the month of

November touring New York; they had the day free on November 19 and

played in Rochester on the 20th.) Other colleges had better luck

booking the Dead, and spring ’71 issues of Pipe Dream had ads for

the nearby SUNY Cortland concert on April 18 (less than an hour's

drive from Harpur). That is, until April 16: “The Grateful Dead

Concert at SUNY at Cortland is SOLD OUT. Please don’t make the trip

unless you already have a ticket.”

(The

Dead wouldn't play in Binghamton again until 1977.)

In the

meantime, bootlegs of the 5/2/70 radio broadcast were starting to

appear by 1971 - incomplete and poorly labeled, but snapped up by the

eager Dead fans who found them. ("We bought any and all Dead

bootlegs, regardless of the quality. We never knew until we got home

to play them. This bootleg was played over and over many times in the

same night for hours at a time...")

Oddly, vinyl bootlegs such

as "Acoustic Dead," "Cowboy's Dead," "Silent

Dead," and "Double Dead" focused mostly on the

acoustic set; as far as I know, only tape collectors (or lucky radio

listeners) would get to hear much of the electric set for many years.

The

show's reputation stayed high - in the '90s it hovered near the top

of Deadbase polls, and on surveys it was a popular request for

release once the Dick's Picks series got started. (One example: "I

had half the show on a cassette since the mid-'70s... They sent out

surveys to ask what our top ten shows were that we'd like to see

released. I filled all ten slots with Harpur College 1970!")

Dick

Latvala himself considered it "the ultimate Dead show" and

"as good as it will ever get." Back in 1977 he'd referred

to it as "this famous date": "There are so many

outrageous things that stand out on this date, that I hesitate to

list them all."

Despite

all the requests, it took a while to show up in the Dick's Picks

series. Latvala had been trying to get Harpur released since the

start. But, as he sighed, "one of the reasons I’ve been

pushing for this one as long as I have...and being rejected for a

long, long time is because of the fact that the electric sets are in

mono. There is a big problem with that."

“Ever

since I got into the position of influence at all, which was when Dan

Healy started the Vault release program in 1990, I’ve been trying

the whole time to get...Harpur College 1970 [out].”

"Harpur

College was rejected every time I brought it up for years. From the

first time I got involved, I was trying to bring Harpur College to

people’s attention and it got beat down every time. It was like a

nightmare to me."

“Anyone

with any common sense knows Harpur College is a show that should have

come out centuries ago. It was ten years of trying to get that one up

the flagpole. Healy would say, ‘That Latvala, he can’t tell the

difference between stereo and mono!’ And that’s why he would

reject Harpur College, cause the electric sets are in mono. So

fucking what? Does anyone say that ain’t a great example of a show?

I’ll tell you, it wasn’t like I snapped my fingers to have it

occur, it was like embarrassing myself forever to get it out.”

Rob

Bertrando recalls, “Phil

absolutely refused to let Harpur College be released with the Cold

Rain & Snow, even after the difficulty getting Cutler to approve

the mono-only electric set.”

Finally

in 1997, the Dead show was released on Dick's Picks 8 (with a few

judicious edits). A caveat emptor on the back cover warned listeners

of the mono electric sets: "While the reason for this remains a

mystery, spurious electrical activity is suspected."

Spurious

or not, electricity was in the air at Harpur that night, and the

tapes captured lightning. Over the years the show became legendary

among Dead collectors, just the word "Harpur" became

shorthand for an intense cosmic journey, and the music would lie in

wait like a timebomb for listeners like me...

“Oh,

what a night in the men's gym!”